If, like me, you’ve thought about the possibility on a semi-regular basis ever since those two classic Doctor Who episodes where David Tennant and Billie Piper come pretty close to experiencing it for real (not really) then this article is about to scratch a near 20-year-old itch.

Now, there are probably plenty of things that NASA has discovered up in space that it keeps under wraps, but the space agency seems more than happy to share information and videos that teach us more about life up in space.

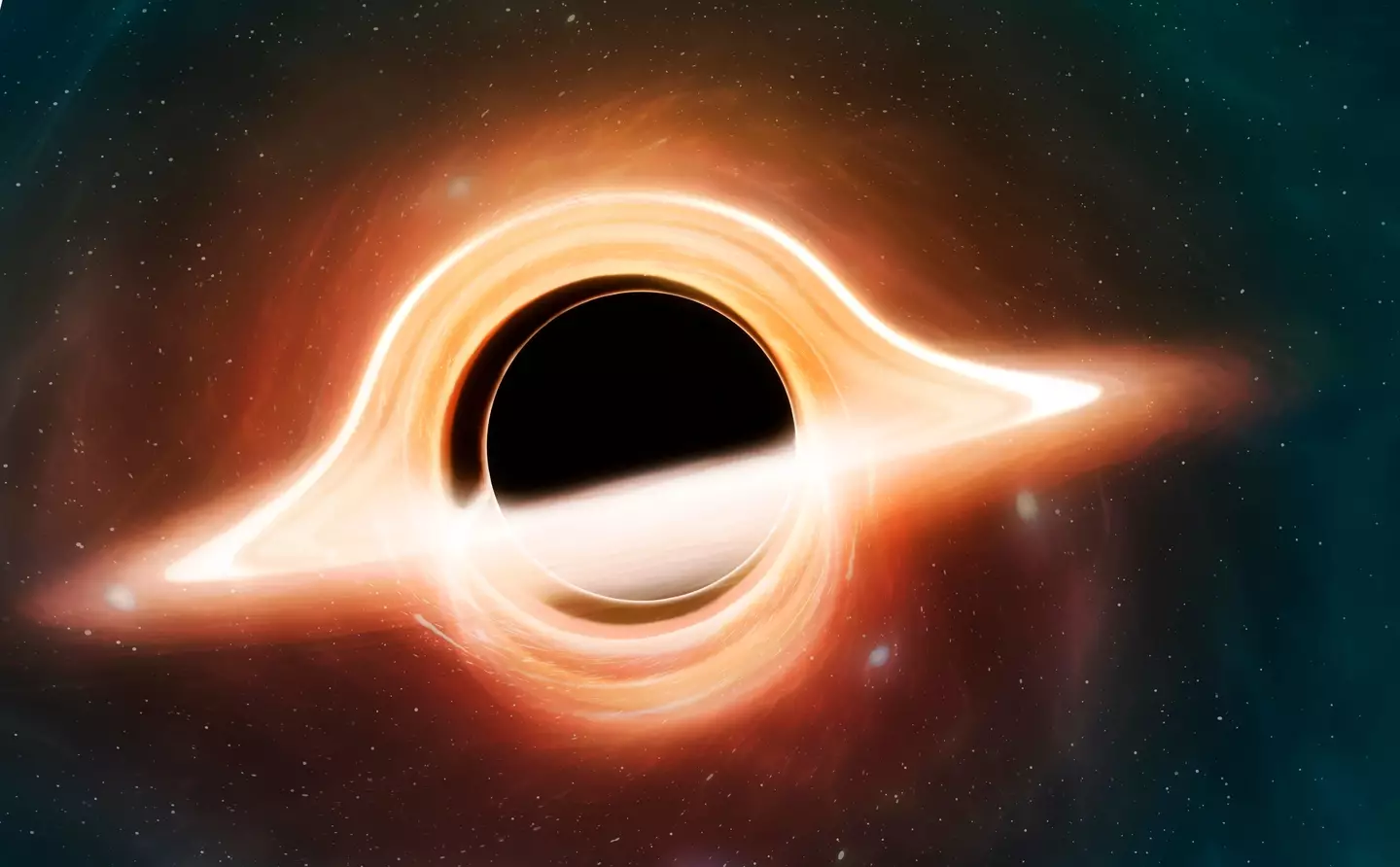

CGI of a supermassive black hole (Getty Stock Image)

Hopefully, none of you ever find yourself in this situation but a simulation, which took NASA’s supercomputers five days to create, has showed us what we can expect if we do ever fall into a black hole.

It turns out Muse knew what they were talking about when calling them supermassive because, according to NASA, they can range from 100,000 to more than 60 billion times our Sun’s mass.

The clip was recently reshared to Instagram by @greatestreactions and viewers have been left stunned.

The visualisation shows a black hole which, according to the account, is similar in size to Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way.

As you approach the hole, time slows down, and just a few seconds for you could be as many as three hours for someone else watching.

So at least it would happen fairly quickly from your own perspective. Once you fully fall inside, you’re enveloped by total darkness as you become one with the black hole, which in some ways is a weirdly romantic way to die.

As good as the scientists at NASA are, they’re unlikely to ever crack the code for what happens next, so that’s the end of the video.

Sadly, flying away from a black hole isn’t as easy without the TARDIS (BBC)

Jeremy Schnittman, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who created the simulation, explained: “If you have the choice, you want to fall into a supermassive black hole.

“Stellar-mass black holes, which contain up to about 30 solar masses, possess much smaller event horizons and stronger tidal forces, which can rip apart approaching objects before they get to the horizon.”